How a Grassroots Student Movement in Bosnia and Herzegovina Fought the System

by Josephine Mintel

(Excerpts from a paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree to the Committee on International Relations, The University of Chicago. Faculty Advisor: Prof. Dr. Maliha Chishti; Preceptor: Manuel Cabal; 2022)

Abstract: Significant obstacles to sustainable peace exist in Bosnia and Herzegovina, partly due to ethnic partitions created by the 1995 Dayton Peace Agreement and the subsequent capture of the government by ethnonationalist politicians. The barriers to peace are exacerbated by the failures of Bosnian government officials and international actors to reform the “Two Schools Under One Roof” policy, segregating public school students based on ethnicity. This article explores a student-led education reform effort in Jajce, an ethnically mixed town in central Bosnia. It provides insights into local attitudes towards ethnic segregation and considers what constitutes a successful, locally-led protest while describing current barriers to education reform. The students in Jajce sought to discourage further ethnic segregation by opposing an extension of the “Two Schools Under One Roof” policy to the high school in their hometown. Later, they protested the “Two Schools Under One Roof” policy in the Cantonal Center of Travnik. The student protest movement in Jajce lies at the nexus of recognizing a distinct ethno-specific identity concurrently with promoting multiculturalism. This seemingly complex intersection is what many have largely failed to understand.

“Every time internationals have talks with our politicians, it’s absolutely necessary to bring young people into the decision-making processes. Currently, we have a council of elders running the country, you know? So young people must be brought to the table.”

– Samir Beharić, a student protest leader from Jajce

High school students during the protest in Travnik.

High school students during the protest in Travnik.

The sign bearing the phrase“IPAK MOŽE ZAJEDNO” (‘nevertheless, we go together) is prominent

.June 20, 2017, REUTERS / Dado Ruvić

The Student-led Protest in Travnik

On a hot summer day in 2017, around 100 young students and activists assembled in front of the Cantonal Ministry of Education in Travnik, the geographical center of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The mood was victorious: two days earlier, the students had won a yearlong battle opposing the opening of a new segregated school in Jajce, a small town in the Central Bosnian Canton. The newly defunct school-to-be would have joined over fifty schools in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which operate under the “Two Schools Under One Roof” (dvije skole pod jednim krovom). In this system, students are segregated based on their ethnic identity. This is one of the most visible threads in the political Gordian knot fettering postwar Bosnia and Herzegovina almost thirty years after signing the Dayton Peace Agreement.

As the crowd coalesced, students chatted animatedly with one another and the myriad national and international representatives. Some students wore paper cutout masks depicting the face of Hrvoje Jurina, a politically appointed school principal in Jajce. He had threatened “severe consequences” to anyone he saw in photos of the Travnik protest. Chants of “zajedno u školu!” (‘together in school!’) erupted periodically, as did enthusiastic renditions of the song Sistem te laže [‘The system is lying to you] by Serbian hip-hop collective Beogradski Sindikat. This song was a mega hit across the Balkans in 2016. Its opening echoes Balkan folk music with characteristic accordion trills and a lilting keyboard ditty, giving way to an intense rhythmic beat. Students emulated the lead rapper, Dare, by emphatically spitting out the chorus:

Sistem te laže,

ne veruj šta ti kaže.

Ovaj život je borba,

od rođenja do groba,

zato ustani odmah!

[The system is lying to you,

don’t believe what it tells you.

This life is a struggle,

from birth until the grave,

so rise up now!]

(Beogradski Sindikat 2016)

The first verse laments that after “wars, protests and reforms, democracy, internet, and new technology, everything is still as it was before” and that “still in the government we have lying puppets, who follow their orders and steal everything for themselves.” The song offers a poignant summation of students’ grievances as they stood united to protest the system perpetuating ethnic division to benefit political elites.

Students also hoisted up banners with slogans like, “Segregation is a bad investment” and, “Are we really doing this in the 21st century?” One particularly eye-catching sign included a colorful mix of pears and apples, reading “Ipak može zajedno!” (“Nevertheless, we go together”). This coy reference demonstrates the lasting impact the words of local politicians have on their citizens. In a remark made nearly a decade earlier, the former Cantonal Minister of Education Greta Kuna stated: “The system of ‘two schools under one roof’’ is good because it prevents pears and apples from mixing” (Vice News, 2014).

Students waited to hear what their Cantonal representative, Katica Čerkez, had to say. As Ms. Čerkez emerged, the crowd flocked around her. She acknowledged that the education system is problematic, but her tone was disparaging as she insisted that Bosnian politicians did not have the power to change the system. She inculpated international actors, blaming the Dayton Peace Agreement and its de facto Constitution as the root of the problem, suggesting that students go “to the disco” instead of wasting their energy fighting a losing battle. She then accused the students of being “instruments of the international community.”

Historical Context: The Break-up of Yugoslavia and the War in Bosnia.

After the end of the Cold War and the death of strongman President Josip Broz Tito, rising nationalism led to the rapid dissolution of Yugoslavia, a country in southwestern Europe with a long history of oscillating ethnocentric dominance. An immediate cause of this disintegration was the Yugoslavian government’s attempts to assert Serbian dominance based on the belief that Yugoslavia’s territory was rightly Serbian. War broke out when some Yugoslavian republics began to secede from the increasingly Serb-dominated central government and create their security forces. While some republics seceded without significant conflict, others suffered bloody wars, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo.

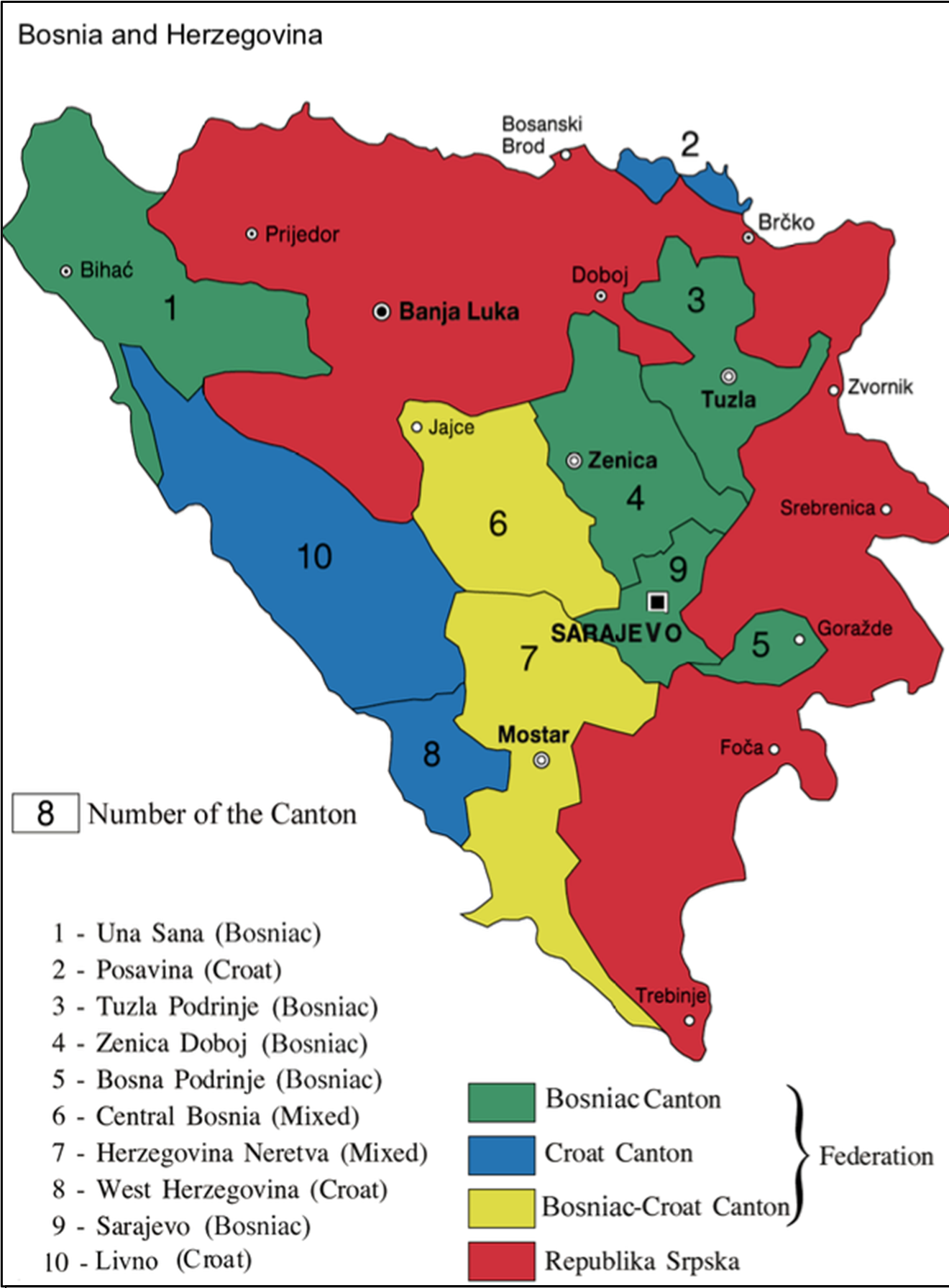

A map of Bosnia and Herzegovina showing Republika Srpska and the Federation.

A map of Bosnia and Herzegovina showing Republika Srpska and the Federation.

Protests took place in Central Bosnia, a mixed-ethnicity canton.

October 3rd, 2003, zegovina / Relief Web.

By 1994, over 200,000 soldiers and civilians in Bosnia and Herzegovina were dead or missing, and an estimated two million became refugees or displaced persons. In 1995, aided by NATO airstrikes, the Croatian military combined with Bosniak troops in a joint offensive against the Serbian army. This led the warring parties to a negotiated ceasefire brokered by the United States and the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement. As the fog of war lifted, Bosnia’s deeply traumatized, ethnically divided, and economically broken citizens began navigating their post-conflict identities.

The Bosnian Context: Liberal Egalitarianism and Ethnic Identity

The Dayton Peace Agreement reduced ethnic identity in Bosnia and Herzegovina to three main categories: Bosnian Serbs-Orthodox Christian (approximately 31% of the population), Bosnian Croats-Catholic (about 15% of the population), and Bosniaks-Muslims (about 51% of the population). Before the war, there were many mixed marriages, and children from those marriages did not fall neatly into the conventional categories. These ethnic and religious couplings are also not universal, and while religion and ethnic identity are inextricably linked for some, religion is immaterial for others. There are also several other ethnic or religious minorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, such as Jewish people, Turks, Romani, and Albanians. Ethnic identity is, therefore, highly individual.

Because there is no “dominant culture” in Bosnia, policies requiring assimilation or a “melting pot” approach are not a reasonable or practical way of dealing with ethnic differences. Two other prominent political theories that deal with organizing diversity are

1. Brian Barry’s (2001) liberal egalitarianism, and

2. Charles Taylor’s (1994) politics of recognition.

Barry’s approach to group diversity is “difference blind.” He argues that different groups can coexist harmoniously if all individuals have equal rights and justice. While he accepts the reality of cultural diversity, he does not believe it should be institutionalized. Charles Taylor’s politics of recognition contends that this “blind” treatment of group diversity is often deaf to the voice of the “other.” Difference blindness, or in his words, “nonrecognition,” often reifies the dominant culture to the detriment of minorities. The politics of nonrecognition can “inflict harm, can be a form of oppression, imprisoning someone in a false, distorted, and reduced mode of being” (Taylor 1994, pg. 25). Therefore, Taylor argues that minorities should be politically recognized through special rights. In Taylor’s view, different groups have the right to educate their children in a way that recognizes their cultural identity, including specialized curricula.

Historical Context: The Education System in Bosnia

During the latter half of the twentieth century, when the Yugoslavian government was operating the education system, nation-building efforts were principally implemented through public education. History education emphasized a Yugoslavia unified by communism, and the schools in what is now Bosnia and Herzegovina were part of this Yugoslavian system. Before the 1992 War, Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks lived and attended school together in relative peace and harmony.

Since the Yugoslavian government used education to further its political agenda, it was easy to use the education system similarly during and after the War. During the War, public education became a network for spreading ethnonationalist ideas. The curriculum was determined by which army controlled the area: Bosnian Serb-controlled areas started using the Serbian curriculum, and Bosnian Croat-controlled areas used the Croatian curriculum. The Bosnian state army rapidly developed a new Bosnian public school curriculum for the places they controlled.

After the War, the institutionalization of ethnic differences in the public education system intensified like those in the political system. Despite education’s critical role in instilling feelings of “brotherhood and unity” in communist Yugoslavia and its cooption for spreading ethnonationalism during the War, the Dayton Peace Agreement did not establish a similarly critical role for public education. Thus, the Constitution gave the central government no direct mandate to control education policy. In addition, international actors in Bosnia and Herzegovina were not immediately tasked with monitoring or implementing education policy.

In 2002, seven years after the end of the War, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) eventually assumed international leadership in the Bosnian education sector. By 2007, the international community’s failures concerning education started to be publicly recognized. The OSCE Head of Mission representative in Bosnia stated:

“The international community failed to respond to wartime curricula that contained messages inconsistent with the Dayton Agreement. It failed to notice that schools began to threaten the country’s long-term peace and stability from the early days of post-war reconstruction.”

The lack of centralized control and attention allowed ethnic segregation and nationalism to take root in the Bosnian education system.

The “TWO SCHOOLS UNDER ONE ROOF” Policy

The international community has often preferred “quick fixes” rather than solutions aimed at longer-term goals in their educational reform efforts in post-conflict situations. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, one such “quick fix” was international support for a system in the Bosnian Federation called ‘Two Schools Under One Roof” (Dvije skole pod jednim krovom). An OSCE address from 2007 states:

“The yardstick for success was merely the number of returnee children attending pre-war schools rather than any change in the things they were learning or in how they were being taught.”

International support for the ‘Two Schools Under One Roof” system in Bosnia and Herzegovina is more understandable in its historical context. The OSCE wanted to encourage as many displaced people as possible to return to their hometowns. The promise that children did not have to attend classes with the “enemy” helped persuade many families to return. Populations seeking to return would request a new “Two Schools Under One Roof” system in their hometown, and the OSCE would facilitate their establishment.

The school in Travnik symbolizes the ethnic and religious divide in Bosnia’s education system:

The school in Travnik symbolizes the ethnic and religious divide in Bosnia’s education system:

Children from Croatian Catholic families attend class on the right side of the building.

On the left, the students are predominantly Muslim.

Credit…Laura Boushnak for The New York Times December 1, 2018

Ethnic segregation in the “Two Schools Under One Roof” program differs by location: sometimes children attend schools in shifts (e.g., Bosniaks in the morning and Croats in the afternoon), and sometimes children attend school at the same time with physical barriers separating them (e.g., barbed wire fencing between playgrounds and separate entrances for different ethnicities). The schools use different textbooks; the students are physically segregated and often exposed to divisive and nationalistic ideologies. Even in so-called “unified” schools, students are separated into different classes for the “national” subjects such as literature, history, and language.

Under the “Two Schools Under One Roof” policy, ethnonational identity in Bosnia became increasingly problematic. Even though Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian are all mutually intelligible variations of the same Southern Slavic language, an essential marker in ethnic identity is which language one identifies as one’s own. (Balkan Insight 2017a). Language is used to define different ethnicities, and variations in the names of places and things have been magnified since the end of the War in 1995. In 2003, the Federation passed legislation confirming students’ right to be educated in their own language and learn so-called “national” subjects, like literature, history, geography, music, and art, according to a curriculum designed for their ethnic group and language. As a result, each curriculum highlights linguistic differences while de-emphasizing similarities.

Dr. Pilvi Torsti (2003, 2007) and Ann Low-Beer (2001) analyzed textbooks and curricula in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Both establish that the curricula in Bosnian schools perpetuate “us” versus “them” narratives. The books containing divisive narratives about the 1992-95 War are phrased as if they continue in the present. For example, a textbook from the Serbian history curriculum describes how “the Serbian people were again forced to defend their honor and dignity with weapons.” It goes on to say: “The Serbian-chetnik genocide against Muslims has deep roots…Serb ideology and politicians have the will to create an ethnically clean territory at any cost.”

Rejection of Ethnic Segregation in Theory, but not Practice

The international community has now distanced itself from the “Two Schools Under One Roof” policy. Several branches of the United Nations, the Council of Europe, and other international bodies have condemned the practice. Soon after student-led protests in 2017, the OSCE issued a report that concluded that the “Two Schools Under One Roof” policy in the public education system in the Federation was discriminatory and contrary to both international and Bosnian laws. This OSCE Report concluded: “Under ‘Two Schools Under One Roof,’ pupils legally can attend either of the two co-located schools, but the practical reality is that the school environments, including curricula, are welcoming to only one ethnic group.” The OSCE report contains the following:

“At present, the situation is not getting better. On the contrary, there was recently an attempt to establish another ‘two schools under one roof’ in Jajce, against the students’ wishes. There are also cases of mono-ethnic schools being established in ethnically mixed areas and students being bused to schools in areas where they are the ethnic majority. These measures will not help the reconciliation process or prepare young people to prosper in the 21st century.”

In 2011, a Bosnian legal aid group, Vaša Prava (with international financial support), filed two discrimination-related court cases challenging the continuation of the “Two Schools Under One Roof” policy. The Vaša Prava lawsuits alleged that the Mostar and Travnik Cantons public schools violated Bosnian and International laws due to ethnic segregation of students. In 2014, the Bosnian Supreme Court held the ‘Two Schools Under One Roof’’ policy in the Stolac and Čapljina schools in the Mostar Canton violated Bosnian and international law. Attempts to enforce this court ruling in Mostar are currently ongoing.

In 2020, The Constitutional Court of The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina also concluded that the school system’s policies in Travnik violated Bosnian and International law. The Court considered three issues raised by the litigants: (1) the physical separation of children of different ethnicities, (2) the single ethnicity of each school’s administration and leadership, and (3) the curricula. In defense of the current system, the school administration and a group of parents who had intervened argued that the “Two Schools Under One Roof” policy was legal because children had a right to be educated in their own language under Bosnian law; the defendant’s position was that this law relating to language created an exception to the prohibitions against discrimination allowing children to be segregated. The Defendants also argued that the ethnicity of school administrators and teachers did not constitute discrimination against students because it was unrelated to the students’ ethnicity. Finally, the defendants argued that there had been significant recent improvements to curricula; because 70% of the curriculum was now “common core,” they asserted that elements of ethnic segregation had already been removed from a large portion of the teaching material.

Despite millions spent by international actors on education programs and the completion of successful litigation, the “Two Schools Under One Roof” program remains prevalent in the central and southern parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Today, there are still 56 schools using this system, and nearly two generations of public school students across Bosnia and Herzegovina have been instilled with “us” versus “them” narratives.

The Beginning of the Protest Movement in Jajce

One of my interlocutors, Samir Beharić, a local activist and alumnus of the Secondary Vocational High School in Jajce, gesticulated wildly as if to sweep his thoughts about his experience in the “Two Schools Under One Roof” system over the ocean between us:

“I would play soccer with my friend, Dragan—I’m Bosniak, by the way, and Dragan is Croat. And so, in the morning, we would play soccer together here in the neighborhood, and then we would go together to our primary school. And then Dragan would basically enter one side of the building, and I would go to the other side of the building, you know, and we wouldn’t even question it. Then, in secondary school, when we started going to school together, then it became a question. Like, how are we here? Why did this happen?”

This demonstrates one of the unique aspects of the education system in the idyllic town of Jajce in central Bosnia, which has around 7,000 residents in the town center and 30,000 in the municipality. While the OSCE received a petition to create “Two Schools Under One Roof” for the primary school in Jajce immediately after the War, they never received a request to segregate the two high schools. Despite being ethnically mixed (with around 45% of the population identifying as Croat, 45% identifying as Bosniak, and 10% identifying as Serb or “other”), both the Jajce Vocational High School and the Nikola Shop High School have operated under a Croatian curriculum since the end of the War.

Samir relates that when he attended high school in Jajce from 2008 to 2012, his curriculum was “pure Croatian.” He learned that Zagreb was his capital, not Sarajevo. Although he is a Bosniak living in Bosnia and Herzegovina, his textbooks were “Croatian.” The curriculum focused on Croatian national narratives. My OSCE interlocutor worked with that organization since 1999, joining the Education Sector when it opened in 2002. When I asked her about the Croatian curriculum in Jajce, she corrected me: “The official name is not the ‘Croatian curriculum’ because this would mean it’s a curriculum of the Republic of Croatia. In our country, it’s called a curriculum in the Croatian language.” Nevertheless, students are taught ethnic narratives in practice despite the OSCE’s attempts to distance the system from ethnonationalist tendencies.

Samir relates that when he attended high school in Jajce from 2008 to 2012, his curriculum was “pure Croatian.” He learned that Zagreb was his capital, not Sarajevo. Although he is a Bosniak living in Bosnia and Herzegovina, his textbooks were “Croatian.” The curriculum focused on Croatian national narratives. My OSCE interlocutor worked with that organization since 1999, joining the Education Sector when it opened in 2002. When I asked her about the Croatian curriculum in Jajce, she corrected me: “The official name is not the ‘Croatian curriculum’ because this would mean it’s a curriculum of the Republic of Croatia. In our country, it’s called a curriculum in the Croatian language.” Nevertheless, students are taught ethnic narratives in practice despite the OSCE’s attempts to distance the system from ethnonationalist tendencies.

Over the summer of 2016, a “petition” was ostensibly submitted to the Central Bosnian Canton requesting a new High School in Jajce that would follow the Bosnian curriculum. One student interviewed called it a “phantom petition.” The representative from the OSCE, who was the most pragmatic of my interlocutors and rarely transcended factual statements, recalled:

“There was constant talk about such a request. But this request was never presented to us. And we believe that it was never put in writing. It was never clear in the whole story who requested it. What we believe is that it was more of a political story.”

The Ministry of Education justified the proposal for a new school based on the legislation in the Federation granting students the right to be educated in their own language and learn “national” subjects based on their ethnic group. However, the motivation for the petition was not to recognize and reify cultural differences. The real reason was likely a tale as old as time—power and money. A new school following the Bosnian curriculum benefited the Croat ethnonationalist politicians on the cantonal level like Ms. Katica Čerkez (from the Croatian Democratic Union of Bosnia and Herzegovina, or Hrvatska Demokratska Zajednica Bosne i Hercegovine, HDZ). Ridding the two current Croatian high schools of Bosniak students would consolidate Croatian power in those schools. There would no longer be any Bosniak students or parents complaining about the lack of Bosniak teachers or the ethnonationalist Croatian curriculum. The new school also favored Bosniak ethnonationalist politicians locally in Jajce (from the Party of Democratic Action, or Stranka demokratske akcije, SDA) because opening a school created a slew of new politically appointed positions for teachers, administrators, and staff. As Samir says, “Here in Bosnia, people don’t get jobs based on merit; they get jobs based on political affiliation. Giving a job to someone means that this person and their family will be indebted, and they will need to return something which is usually, if not money, then with their vote.”

In a precarious job market, a position in a school is one of the most common forms of public employment in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Public school employment makes up over 54% of public sector jobs (Education Statistics | Bosnia and Herzegovina). Although the student-led protests eventually stopped the new Bosniak-run school from existing, board members of the non-existent school had already been “hired.” All five board members were members of the SDA Bosniak nationalist party. Ms. Katica Čerkez insisted that this is not segregation based on ethnicity because students can enroll in whichever school they choose. However, by law, the ethnic makeup of school boards in Bosnia must reflect the makeup of the student body, and it is clear what ethnic makeup the local politicians anticipated. School budgets would also be split among the three schools. Instead of investing money in repairing existing infrastructure or buying more books and materials, the money would go into wages. Those wages then supply the political parties with more money and votes, continuing the cycle.

In response to the “phantom petition,” students from the two high schools in Jajce prepared and submitted their own petition to the Central Bosnia Canton opposing the creation of the new school. The student petition contained two additional requests. First, the students wanted options in the diplomas awarded upon graduation; previously, all diplomas depicted a Croatian Coat of Arms. Students requested a choice of a Croatian-style diploma or a Bosniak-style diploma. Second, the students asked for an expansion of the “national” group of subjects from two classes (language and religion) to five (language, religion, history, music, and geography). These two requests were an explicit acknowledgment of ethnic differences. Although students would not be segregated under their proposal, there would be increased “soft” institutionalization of ethnic differences.

After the students filed their petition with Central Bosnian Canton, the community and the school debated the proper course of action. Several teachers organized a survey for students, parents, and teachers in Jajce, asking them for their opinions on how the Ministry of Education should proceed (Balkan Insight 2017b). Survey participants could choose among three options: 1. establishing the proposed new segregated high school with a Bosniak curriculum, 2. keeping the status quo by maintaining the Croatian curriculum in the two current high schools, or 3. developing a new integrated curriculum inclusive of all the ethnic groups in the two current high schools. The overwhelming majority voted for the third option.

Samir Beharić asserts that the students requested the expansion of national subjects as a compromise; he said they knew it would be difficult to win the battle against ethnonationalist politicians without such a request. For the students, expanding the national subjects so Bosniak students could choose courses that recognized their ethnic identity was preferable to the sole availability of a curriculum in Croatian. However, the students saw the potential for creating a unified curriculum recognizing each ethnic group. For the students, valuing ethnic identity and attending a multicultural school were not incompatible.

The first protest in Jajce happened almost a year before the rally in Travnik. It was much smaller, with about a dozen students marching from the Vocational High School to the Nikola Shop High School through Jajce’s city center on July 8, 2016. Nikolas, a student from the Vocational High School and one of the core members of the protest group, told me about the protest focusing first, not on the students’ raw enthusiasm or meeting with “the big boys,” as he refers to prominent international stakeholders, but the controversy over the flags brought to the protest.

Credit: Jajce student Facebook page

Credit: Jajce student Facebook page

In what the students thought was a show of solidarity and promotion of multiculturalism, they brought to the protest the Serbian flag, the Croatian flag, and the flag of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina. When photos with the flags appeared in local media after the protest, it “diminished the students’ message,” according to my interlocutor from the OSCE. Some Bosniaks and Serbs were upset about the Croatian flag. Some Bosniaks and Croats were upset about the Serbian flag. Members from all three groups were upset about Bosnia’s “quasi-European” flag, which has a triangle representing the three constituent peoples and uses yellow stars with a blue background reminiscent of the E.U. logo. While some (mainly Serbs and Croats) feel that this flag represents the “internationally supported” Muslim-Bosniak cause during the War, some Bosniaks feel this flag was pushed on them by internationals usurping the traditional Bosniak flag, which has a blue shield decorated with lilies. However, Nikolas argues that critics failed to realize that the students also chose to carry a Serbian flag, even though no Serb students were present at the protest (they were all on summer vacation). It was a Croat boy carrying the Serbian flag through the streets of Jajce that day. The media never highlighted this symbolic act of unity, which local commenters and international stakeholders also overlooked.

Samir maintains that the OSCE was “mostly deaf” to their calls for support in the early months of the movement. My interlocutor from the OSCE insisted that they had supported the student protesters “from the moment it started” and that Johnathan Moore, the Head of Mission at the OSCE, had been “heavily invested” since he met with the students before their first protest of July 8, 2016. When I asked my interlocutor from the OSCE if Ambassador Moore had “pressured” local authorities to accede to the student demands, she said, “I’m not sure that I would call it ‘pressure.’ I think the OSCE’s approach was that everybody knows about the students and their demands.” The OSCE’s initial hesitancy and lack of full-throated support likely stemmed from the “parade” of ethnonationalist symbols (i.e., the flags). However, celebrating each other’s ethnic identities through the flags symbolized unity for the students.

Samir called Johnathan Moore out in an article he wrote for a local news outlet in the spring of 2017:

“OSCE Ambassador Jonathan Moore has been involved in the struggle of high school students from the beginning, but for too long, he has been too lenient towards the main culprits who want Jajce to take a civilizational step backward. Ambassador Moore should know that his negotiators in Jajce and Travnik are not foreign ambassadors but former war generals, soldiers, and politicians hardened in lies who have been in politics for two decades and have long since become distant from their people. What is missing is political pressure to will the authorities to take the next step towards integrating education, which they will obviously not do alone.” (Beharić 2017)

Samir tells me the type of rhetoric he had hoped for eventually came from the Canadian Ambassador, who had been alerted to the student movement by the OSCE. She told local politicians they would segregate the schools “over her dead body.” While the OSCE support was more of a slow burn than a spectacular blaze, they did facilitate the meeting in June 2017 between the Ministry of Education’s Katica Čerkez and the students. However, it took almost a full year from the first protest march in Jajce for that meeting to occur.

In the end, the three demands contained in the student petition were satisfied: the new high school was not opened; the students were given a choice of diploma, and the “national” subjects were expanded from two classes (language and religion) to five (language, religion, history, music, and geography). These three demands demonstrate that the students valued their ethnic identity and wanted to learn about their own language, religion, and culture. However, they did not see this as an excuse for more ethnic segregation.

Unlike the negotiators in Dayton, Ohio, the students strove both to achieve equal rights for all as per the system of liberal egalitarianism promoted by Brian Barry and to preserve recognition of ethnic differences consistent with Charles Taylor’s politics of recognition. They did not want to learn ethnonational narratives at the expense of other ethnicities; they wanted to celebrate their differences together. Like the carrying of the flags, this request can be superficially confusing. The Jajce student’s convictions lie at the nexus of recognizing ethnic identity and promoting multiculturalism; this seemingly discordant intersection is what some internationals struggled to understand.

Evaluating the Role of International Actors

As in other areas of peacebuilding, international actors must broaden their view of what is likely to impact the day-to-day working of post-conflict education systems by recognizing and responding to the opinions of those directly involved. In Briony Jones’ (2012) piece on education in the ethnically mixed Brčko district in Bosnia, she argues that internationals must “listen to the voices of the teachers and students themselves and seek to understand their experiences.” She continues: “…despite their ability to tell us about the meaning and effectiveness of reform processes, they are the voices which are the least heard in the discourse on education policy in postwar countries.” (p. 133).

The United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 2250 in 2015, which recognizes “the importance of engaging young women and men in shaping and sustaining peace” (“U.N. Youth, Peace, and Security,” 2015). As a result, there has been an uptick in civil society-led conferences and projects bringing together young people from different ethnic backgrounds and focusing on peace and human rights education outside public schools. However, Nicholas Micinski (2016) argues that international organizations in Bosnia recruit the same “NGO frequent flyers” in their youth-focused projects, contributing to an elitist environment that does not reach the general population. Micinski remarks that these “NGO frequent flyers” raise three critical considerations:

“First, they legitimized the liberal peacebuilding agenda by providing a façade of local participation and ownership. Second, they provided biased intelligence about the situation on the ground because NGO frequent flyers, and civil society in general, reflected back to donors what they wanted to hear in order to continue receiving funding. Third, while NGO frequent flyers were genuine participants, the true targets of reintegration projects were nationalist youth and their families who do not support the liberal peacebuilding agenda.” (p. 102)

This accentuates the critical need for public education reform, which can impact youth on a broader scale than boutique youth and reconciliation panels and workshops that only reach a certain educated elite. Thus, international support of public education students and their attempts to reform the public education system like the Jajce students is paramount.

The students who organized and led the education reform movement in Jajce were given the Max van der Stoel Award in November 2018 (Balkan Insight 2018). This award recognizes “extraordinary and outstanding achievements in improving the position of national minorities” in OSCE member states and is sponsored by the OSCE’s High Commissioner on National Minorities. It comes with a 50,000-euro prize. The money associated with this award was destructive to student solidarity as squabbles broke out among students about how it should be spent.

The need to examine and understand how international actors can support local reform movements in the peacebuilding context is particularly acute in the post-war education reforms in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the case of the Jajce student-led reform effort, international actors made several missteps, including the failure to listen to and understand students’ reform efforts and support them throughout their struggles. Also, awarding a large monetary prize in a way that became divisive and destructive of student unity was not constructive. Given the difficulties encountered with enforcing favorable court judgments, it is unclear whether the international help with financing the litigation brought by Vaša Prava is a productive endeavor.

Evaluating the Success of the Student-Led Movement

On the surface, it is easy to conclude that the 2016-17 student protests in Jajce and Travnik were both a success and a failure. In Jajce, all three elements in the petition submitted by the students were granted: a new segregated school was not opened, the students were given a choice of diplomas, and the number of “national subjects” expanded. This can be categorized as a complete success from the students’ point of view. This is true even though the second and third items were proposed as “compromises” and recognize separate ethnic identities. In Travnik, the protests did not result in immediate change: the Travnik schools remained segregated. Thus, this result could be categorized as a failure on the surface.

The literature evaluating the success or failure of a particular attempted local reform effort must also be considered when assessing the success or failure of these efforts. Karen Ross, Charla Burnett, Yuliya Raschupkina, and Darren Kew (2019) provide a conceptual model for evaluating peacebuilding and social justice work. They propose “…broadening scholars’ understanding of the success of nonviolent movements not only by analyzing the size of territorial span of the movements” but also by “…discussing societal changes that the very actions of social movement facilitate, regardless of whether the movement fails or succeeds in achieving its goals” (p. 497). In addition, they explore methods for evaluating a particular movement, including how it promotes the internal strength and external expansion of an idea and how the process can be extended through building coalitions across campaigns. Rather than viewing reform efforts as a linear or chronological process, their model promotes an “impact-oriented and an iterative process of social learning, where actions are shaped by reactions (by the government and other actors) to previous moves” (p. 497).

When using these theoretical models for assessing peacebuilding and social justice work, the student-led protests in Jajce and Travnik take on a much more successful sheen. The Jajce students got positive reactions from some of their teachers and parents through the teacher-led survey that was developed and published. They also ultimately recruited the OSCE to their side. The response of school administrators was not initially positive, but at least in Jajce, the school administration agreed to the changes the students proposed. The students learned more about successful messaging through the adverse reaction to their attempts to show solidarity using national flags.

The protest in Travnik involved more people, another sign of success even though nothing in Travnik seemed to change. At least two subsequent developments after the Travnik protest are indicators of the success of this phase of the student protests. These are 1. the change in position by the OSCE and other international actors from initially supporting the “Two Schools Under One Roof” policy to actively opposing it, and 2. The favorable court ruling in the lawsuit filed by a local legal aid group with international support against public school policy in Travnik; the Court held that the segregated schools in Travnik violated Bosnian and international law. These developments indicate that the student protests had an impact, and an iterative action and reaction began.

Conclusion

My interlocutor, Samir, enthusiastically supported school integration, multiculturalism, and democratic values. So, when he was talking to me about his history classes during his primary school years in Jajce, I was slightly taken aback as he went on a diatribe about Jajce’s history and his own ethnic identity:

“Through the window of my history classroom, we could see the fortress of the last Bosniak King because Jajce was the stronghold and former capital of the [Bosnian] Kingdom. And it was in 1463, in May when the Ottomans came to Bosnia. When Jajce fell, the Bosnian Kingdom fell, and when the Bosnian King Stefan Tomašević was taken hostage and killed in Jajce, this was the end of the Bosnian Kingdom. So, the capital of the Bosnian Kingdom was in this city, and through the windows of our classroom, we looked at the last fortress of the Bosnian Kingdom but didn’t learn anything about it. It was as if it didn’t exist, you know. Instead, we were learning about Croatian history and the Croatian kings. We were learning about a neighboring country.”

Samir’s insistence on relaying this to me underscores the ubiquity of ethnic narratives in Bosnia and Herzegovina. He hesitated when asked where he learned this history, if not in school, and felt he had always known. Finally, he decides that his parents must have taught him this as a child. This was also the anecdote through which I realized that valuing ethnic identity and advocating for integration and multiculturalism are not mutually exclusive ideas, particularly among the young activists and students in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Only the political elites, who profit from segregation and identity politics at their worst, find them incompatible. Then, when confronted with a grassroots peacebuilding movement, international actors could not reconcile a simultaneous embrace of ethnic identity and multiculturalism. Instead of the enthusiastic support of a locally-led solution devised by youth, they hovered at “diplomatic neutral.” These young students and activists in Bosnia and Herzegovina embody both ideals and understand “ipak može zajedno” (Nevertheless, they go together).

Wall graffiti during the student protests: “Zajedno stvaramo” or “We create together.”

“Notes:

The methodologies used in this research are a combination of semi-structured interviews, historical research, and discourse analysis. Descriptions of the protests come from my interviews with participants as well as observations by Piersma (2019).

“Bosnia” is used in this paper as a short form of “Bosnia and Herzegovina” where stylistically appropriate. This is with no intent to ignore the culturally rich and historical region of Herzegovina.

REFERENCES

Balkan Insight. 2016. “Bosnia’s Segregated Schools Perpetuate Ethnic Divisions.” July 15, 2016.

https://balkaninsight.com/2016/07/15/bosnia-s-segregated-schools-perpetuate-ethnic-divisions-07-15-2016/

Balkan Insight. 2017a. “Pupils Challenge Ethnically-Divided Education in Bosnia.” June 12, 2017.

https://balkaninsight.com/2017/06/12/students-challenge-ethnically-divided-education-in-bosnia-06-12-2017/.

Balkan Insight. 2017b. “Bosnian Pupils Rally Against Ethnic Segregation in Schools.” June 20, 2017.

https://balkaninsight.com/2017/06/20/bosnian-pupils-rally-against-ethnic-segregation-in-schools-06-20-2017/.

Balkan Insight. July 2018. “Bosnian School Children win Award for fighting Ethnic Segregation in Schools.”

https://balkaninsight.com/2018/07/20/pupils-from-bosnia-win-max-van-der-stoel-award-07-19-2018/

Barry, Brian. 2000. Culture and Equality: An Egalitarian Critique of Multiculturalism. 1st edition. Cambridge: Polity.

Beharić, Samir. “Samir Beharić: Dvije mature pod jednim krovom.” Klik Jajce (blog), May 16, 2017.

https://www.klikjajce.com/samir-beharic-dvije-mature-pod-jednim-krovom-2/.

Brljavac, Bedrudin. 2018. “Alone against the Political Discourse: Jajce High School Students against the Ethnic Segregation.”

“Dayton Peace Agreement.” 1995. https://www.osce.org/bih/126173.

Diegoli, Tommaso 2007. “Collective Memory and Social Reconstruction in Post-conflict Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH).” Graduate School of International Studies. The University of Denver. Unpublished thesis.

Hamilton, Daniel S. 2020. “Fixing Dayton: A New Deal for Bosnia and Herzegovina |

Wilson Center.” https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/fixing-dayton-new-deal-bosnia-and-herzegovina.

Hartwell, Leon. 2019. “Conflict Resolution: Lessons from the Dayton Peace Process.” Negotiation Journal 35 (4): 443–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/nejo.12300.

“Jajce | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Britannica.” n.d. Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/place/Jajce.

“Jajce: Učenici Složni, ‘Ne Želimo Podjele.’” n.d. BN. Accessed May 2, 2021. https://www.rtvbn.com/3824185/jajce-ucenici-slozni-ne-zelimo-podjele.

Jones, Briony. 2012. “Exploring the Politics of Reconciliation through Education Reform: The Case of Brcko District, Bosnia and Herzegovina.” INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE, no. 1: 126.

Komatsu, Taro. 2019. “Integrated Schools and Social Cohesion in Postconflict Srebrenica: Bosniak Youths’ Views of Their Schooling Experiences.” Comparative Education Review 63 (3): 398–417. https://doi.org/10.1086/704112.

Low-Beer, Ann. 2001. “Politics, School Textbooks, and Cultural Identity: The Struggle in Bosnia and Hercegovina.” Internationale Schulbuchforschung 23 (2): 215–23.

Micinski, Nicholas R. 2016. “NGO Frequent Flyers: Youth Organisations and the Undermining of Reconciliation in Bosnia and Herzegovina.” Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 11 (1): 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/15423166.2016.1143783.

OSCE. 2018. “‘Two Schools Under One Roof’ – The Most Visible Example of Discrimination in Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina.” Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.osce.org/mission-to-bosnia-and-herzegovina/404990.

Perry, Valery. 2003. “Reading, Writing and Reconciliation: Educational Reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina – European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI).” Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.ecmi.de/publications/ecmi-research-papers/18-reading-writing-and-reconciliation-educational-reform-in-bosnia-and-herzegovina.

Piersma, Michiel J. 2019. “‘Sistem Te Laže!’: The Anti‐ruling Class Mobilisation of High School Students in Bosnia and Herzegovina.” Nations and Nationalism 25 (3): 935–53.

“Pirova Pobjeda Učenika Iz Jajca: Škola Za Bošnjake Je Već Osnovana, Počinje s Radom Naredne Godine.” 2016. Klix.Ba. 2016. https://www.klix.ba/vijesti/bih/pirova-pobjeda-ucenika-iz-jajca-skola-za-bosnjake-je-vec-osnovana-pocinje-s-radom-naredne-godine/160815029.

Premilovac, Aida. 2007. Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina: A Neglected Security Issue ‖ Speech at the OSCE parliamentary conference held in Slovenia from Sept. 29 to Oct. 1.

Press, Jajce. 2017. “Samir Beharić: Dvije mature pod jednim krovom.” Klik Jajce (blog). May 16, 2017.

https://www.klikjajce.com/samir-beharic-dvije-mature-pod-jednim-krovom-2/.

Pugh, Michael. 2002. “Postwar Political Economy in Bosnia and Herzegovina: The Spoils of Peace.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 8 (4): 467–82. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-00804006.

Richmond, Oliver P., and Jason Franks. 2009. “Between Partition and Pluralism: The Bosnian Jigsaw and an ‘Ambivalent Peace.'” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 9 (1–2): 17–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683850902723389.

Roberts-Schweitzer, Eluned, Vincent Greaney, and Krezentia Duer. 2006. Promoting Social Cohesion through Education. World Bank Institute Resources. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-6465-9.

Ross, Karen, Charla Burnett, Yuliya Raschupkina, and Darren Kew. 2019. “Scaling‐Up Peacebuilding and Social Justice Work: A Conceptual Model.” Peace & Change 44 (4): 497–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/pech.12371.

Smith, Alan, Erin McCandless, Julia Paulson, and Wendy Wheaton. 2011. “The Role of Education in Peacebuilding: Literature Review | Education in Crisis and Conflict Network.” Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.eccnetwork.net/resources/role-education-peacebuilding.

Taras, Ray. 1999. Review of Making a Nation, Breaking a Nation: Literature and Cultural Politics in Yugoslavia. Cultural Memory in the Present, by Andrew Baruch Wachtel. Canadian Slavonic Papers / Revue Canadienne Des Slavistes 41 (3/4): 498–500.

Taylor, Charles. 1994. The Politics of Recognition. Multiculturalism. Princeton University Press. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781400821402-004/html.

Torsti, Pilvi. 2003. “Divergent Stories, Convergent Attitudes : Study on the Presence of History, History Textbooks and the Thinking of Youth in Post-War Bosnia and Herzegovina,” December. https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/12165.

Torsti, Pilvi. 2007. “How to Deal with a Difficult Past? History Textbooks Supporting Enemy Images in Post‐war Bosnia and Herzegovina.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 39 (1): 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270600765278.

Torsti, Pilvi. 2009. “Segregated Education and Texts: A Challenge to Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina.” International Journal on World Peace 26 (2): 65–82.

“Vasa Prava Press Release,” July 23, 2021. https://pravnapomoc.app/en/newsdetails?id=44.

Vice News. 2014. “Bosnia-Herzegovina Court Orders End to Ethnic Segregation of Schoolchildren.” https://www.vice.com/en/article/438m9n/bosnia-herzegovina-court- orders-end-to-ethnic-segregation-of-schoolchildren.

World Bank. 2012. “Education Statistics | Country – Country at a Glance – Bosnia and Herzegovina.” World Bank. 2012. https://datatopics.worldbank.org/education/country/bosnia-and-herzegovina.

Yordan, Carlos L. 2003. “Society Building in Bosnia: A Critique of Post-Dayton Peacebuilding Efforts.” Seton Hall Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations 4 (2): 59–74.

“Youth, Peace and Security | PEACEBUILDING.” Accessed January 23, 2021.

https://www.un.org/peacebuilding/policy-issues-and-partnerships/policy/youth.